"Graphic" vs. "Illuminated"

Lehrer brings up an interesting point about our categorization of books and the labels we use to identify different book formats. A “graphic” novel taken literally would imply some use of visual art as an illustrative device to enhance the book’s content, and would encompass a wide variety of book design formats: engraving, lettering, illustrations, graphics, etc. Yet our use of the label “graphic novel” in the book community has stripped “graphic” of its broader implications. Now the term applies to a specific format - a comic in book length with cartoon illustrations and thought bubbles - to the extent that the term “graphic” would be misleading on the cover of A Life in Books, despite being technically very applicable.

The appropriation of the term “graphic novel” as the comic book genre’s label can be somewhat traced through the 1900s, but was firmly established following the publication of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in 1986. Classics such as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000) and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006) have further entrenched the graphic novel into the mainstream book community.

For more about the history of the graphic novel, check out this slideshow by Abby Connolly.

Feature

An Interview with Award-Winning Author Warren Lehrer

Part 2 of 2

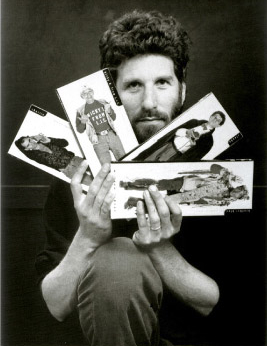

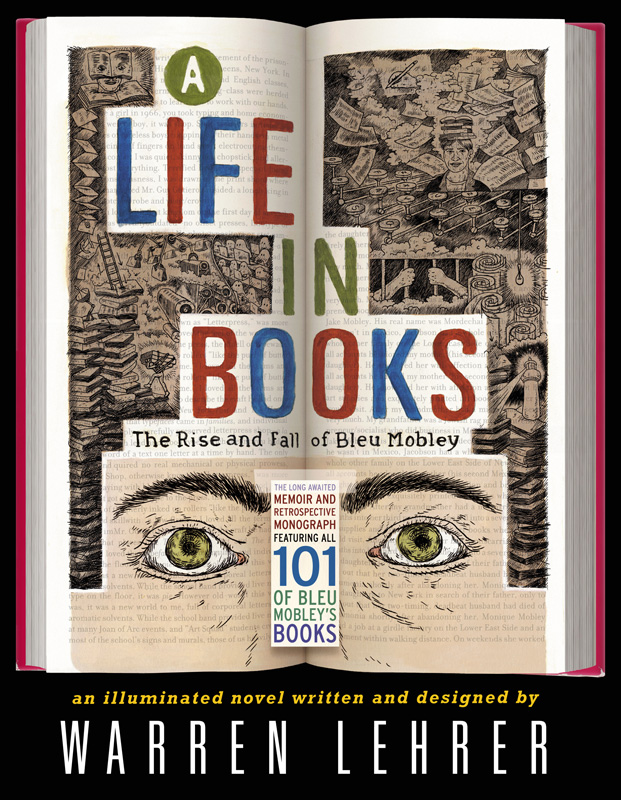

IP got the chance to speak with award-winning author Warren Lehrer about his incredibly unique novel, A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley (Goff Books), which follows the career of fictional author Bleu Mobley all the way through youth to success, fame, and eventual downfall.

With A Life in Books, Lehrer has upended the modern novel form and its narrative limitations, creating a rich and engaging story through visual literature. In the second of a two-part interview, Lehrer gives us insight into his creative take on the novel format and the publishing industry trends that impact Bleu's career (Click here to read Part 1 of the interview).

Although Bleu’s story is wrapped up in his writing, the book is not simply confined to his words; each book’s exact presentation to the public is detailed, from the physical appearance to the catalog copy. What is the significance of the books’ delivery/packaging for mass consumers and media?

Things often come to me backwards, or inside out. Usually, when you think of book design you think of the cover art. That’s certainly true of novels and other text-laden books, whose insides are usually made up of gray slabs of text. When I first started writing and designing my books, I was entirely concerned with the interior of the book, its content and form. When it came to the covers, I struggled mightily, and resented having to distill/stereotype the contents into a single image or identity.

Things often come to me backwards, or inside out. Usually, when you think of book design you think of the cover art. That’s certainly true of novels and other text-laden books, whose insides are usually made up of gray slabs of text. When I first started writing and designing my books, I was entirely concerned with the interior of the book, its content and form. When it came to the covers, I struggled mightily, and resented having to distill/stereotype the contents into a single image or identity.

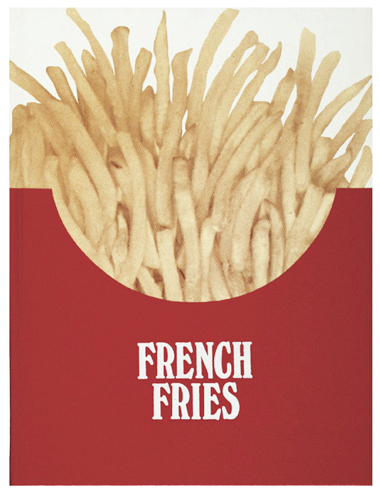

After a while, I found myself envisioning the covers of my books before writing them, which is also kind of backwards, or inside out. A book by it’s cover, and all that. Moments after Dennis Bernstein and I had the idea of writing a book/play that takes place in an American fast food joint, we came up with the title French Fries, and moments after that I sketched a cover design that looked like a box of McDonalds’ French fries.

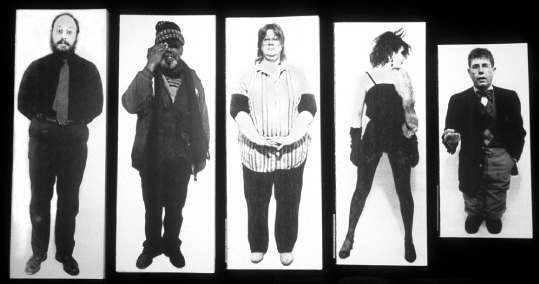

Original dummies for The Portrait Series.

When I came up with the idea to write portrait books documenting American eccentrics, I envisioned a suite of books proportional in size to the human figure, with a photograph of each subject from the front on the front cover, and a photo of them from the back on the back, and inside would be the guts told in first person monologues. The covers and format became the mission statement for the books that were yet to be written.

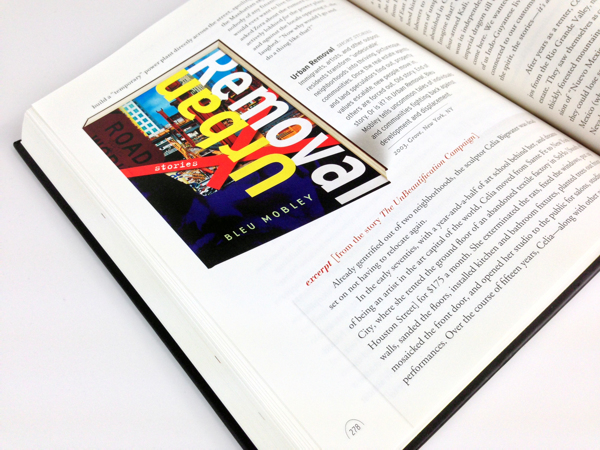

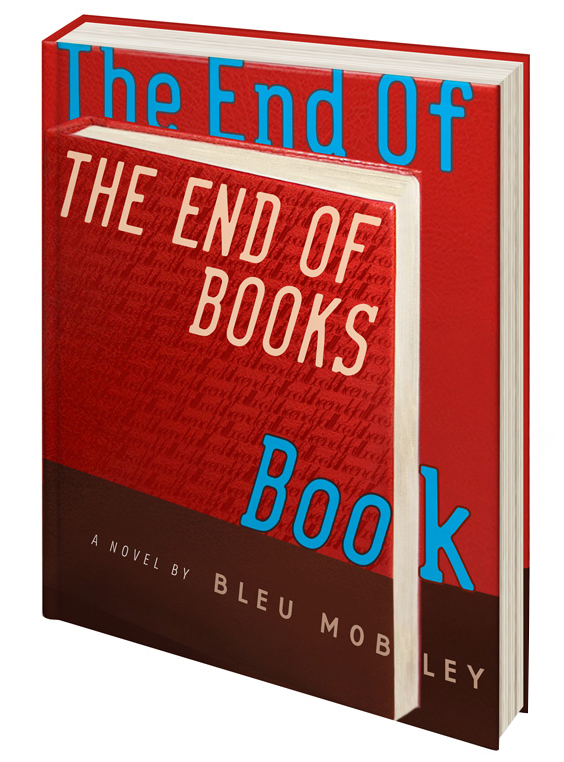

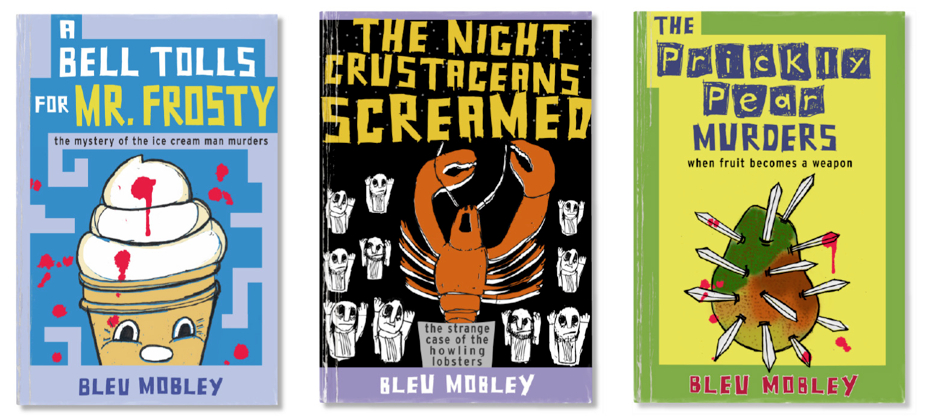

For A Life In Books, I knew I had over 101 book covers to design. They didn’t come easy, but I loved working and reworking them till they felt right, were in keeping with Bleu’s style (he designed all his own covers), and seemed plausible for the time period. Most delightful for me, the covers didn’t really have to function as marketing tools or as packaging, but were part of the novel’s content, which meant they were sometimes commentary (on marketing, packaging, the publishing industry), and sometimes metaphorical or allegorical expressions of what was going on with Bleu, or one of his friends or relatives, or the world at that time.

For A Life In Books, I knew I had over 101 book covers to design. They didn’t come easy, but I loved working and reworking them till they felt right, were in keeping with Bleu’s style (he designed all his own covers), and seemed plausible for the time period. Most delightful for me, the covers didn’t really have to function as marketing tools or as packaging, but were part of the novel’s content, which meant they were sometimes commentary (on marketing, packaging, the publishing industry), and sometimes metaphorical or allegorical expressions of what was going on with Bleu, or one of his friends or relatives, or the world at that time.

I began this project with a rough outline of Bleu’s story, and a dozen or so book titles. As soon as I started writing his narrative, finding his voice, I also started sketching some of his book jackets. Then the jacket covers helped me have a better understanding of what the books were about, and I set about writing book excerpts, each of which had to have an arc of some kind, like a short story, but leave you feeling like it could have been excerpted from a larger book.

The most surprising part of the process for me was how the Mobley book excerpts started cluing me into things about Bleu and his story that I hadn’t anticipated. The two realms kept informing each other, until it wasn’t a puzzle for me anymore and the entire picture came into focus.

The most surprising part of the process for me was how the Mobley book excerpts started cluing me into things about Bleu and his story that I hadn’t anticipated. The two realms kept informing each other, until it wasn’t a puzzle for me anymore and the entire picture came into focus.

The design of A Life In Books distinguishes Bleu’s narrative from the book excerpts, the cover designs, and catalogue descriptions. While most of the excerpts are set onto light gray pages that give you the feeling of reading a book within a book and are said to be “reformatted” for A Life In Books—excerpts with pictures in them or very particular typography are presented as “reproductions” from the actual books. There are also “reproductions” of letters, posters, and snidbits of book reviews, newspaper and magazine articles, FBI files, and grant applications.

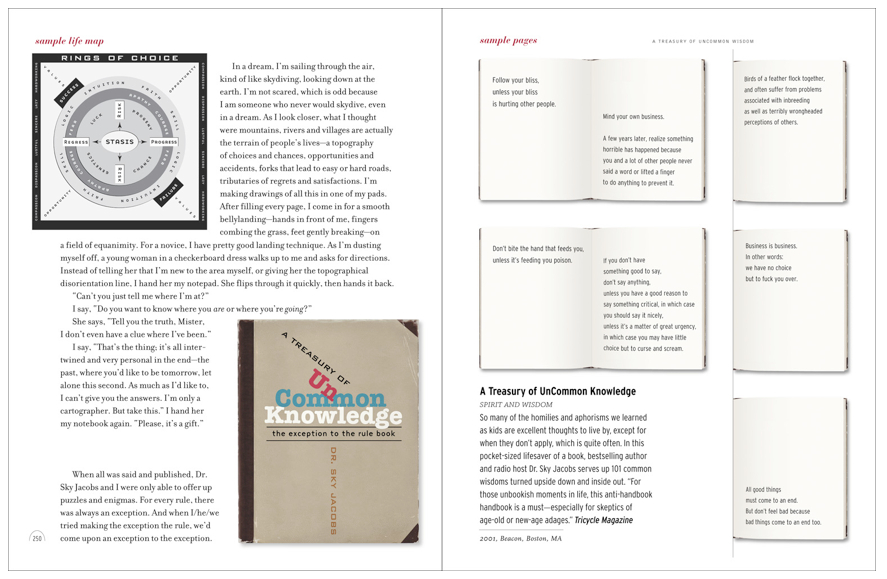

Page spread from A Life In Books featuring a map for Dr. Sky Jacobs’ Life Maps, and pages from his UnCommon Knowledge.

A Life in Books is a stunningly unique take on the novel format compared to the standard in today’s publishing world; the book’s design is a fresh reimagining of the kind of illustrated fiction that was so popular in the 1800s. How do you think your take on “visual literature” expands the novel as a medium, and what role do you think it plays in contemporary publishing?

I would just call A Life In Books a graphic novel, but the term is already taken. I love the work of Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman, Joe Sacco, Alison Bechdel, and admire the way each of them have expanded the graphic novel tradition to tell true, important stories in compelling ways. But I don’t draw characters and use speech and thought bubbles. That’s not what I do.

By calling A Life In Books an “illuminated novel” I beckon back to illuminated manuscripts, when incredible artistry and craft went into making books, and color and shape and images intertwined with the text. I’m not all that interested in the decorative aspects of medieval manuscripts, but I am very much interested in examples that are polyvalent, like the Talmud which has a source text from the Torah in the middle, and liberal and conservative rabbi’s expounding and debating in the surrounding columns, flanked by footnotes and other marginalia. Hypertext is alive and well in many of those meticulous, sacred manuscripts.

I choose to call A Life In Books an illuminated novel primarily because Bleu’s narrative is illuminated by his life’s work. Together they add up to tell his story. In the popular illustrated fiction of the 1800s that I know of, like serialized editions of Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and A Christmas Carol, the drawings illustrate scenes from the writing. Publishers went for it because photomechanical processes had gotten much more affordable, and it was satisfying for readers to see what the characters, places, and action scenes looked like. At their best, the illustrations helped establish mood. But the novelty wore off after a while, and illustrated fiction went out of fashion, for good reason—it’s redundant to see the picture of what you just read or are about to read. That makes sense in books made for young children learning how to read. They see the word tree, and then they see a picture of a tree.

In the same way that Bleu’s writings don’t merely mirror his life, the images and visuals in A Life In Books, at their best, are not duplicative of the text. The images are part of the text, and the different kinds of texts (and “artifacts”) work together to paint the picture.

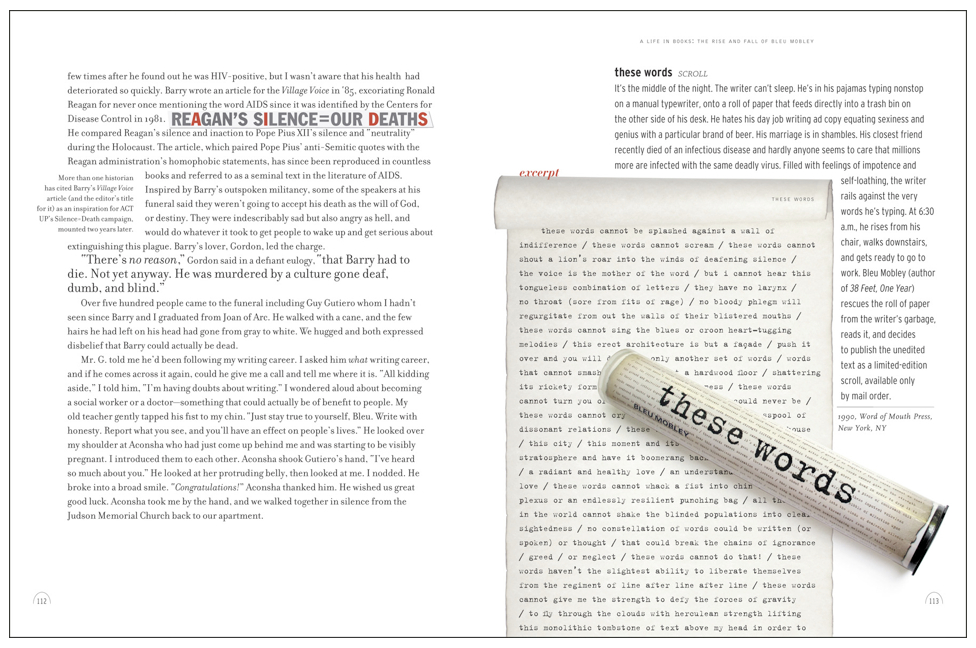

A page spread from A Life In Books featuring Bleu’s limited edition scroll these words, circa 1990.

The tradition of Visual Literature that I come out of connects more to the revolutionary “experiments” from the early part of the 20th century by Mallarmé, Apollinaire, Marinetti, the Dadaists and Futurists, who wrote and designed manifestos and made books that broke from traditional syntax and columns of text, and imagined a new kind of literature that didn’t only evoke experience but created it, and in so doing related the placement of words on the page to their meaning.

But that revolution never really took hold within the literary world. Over the past century there continued to be iconoclasts like Kenneth Patchen, movements like Fluxus and Letterists, and artist book practitioners generally acknowledged more within the fringes of the visual art world than within the publishing industry whose gatekeepers have remained very conservative when it comes to form and genre. Only now—that the second wave of the digital revolution threatens the book (as we have known it), and writers have all kinds of writing machines at their disposal—are more and more odd-looking novels and works of visual literature finding their way into the hands of readers. Go into your favorite independent bookstore or Barnes and Noble, and you’ll find approximately one out of fifty novels that have something visual going on between their covers—instead of one out of a thousand! It’s as if the revolution that Stéphane Mallarmé wrote about in his 1898 essay The Book As Spiritual Instrument is finally starting to take hold. It’s a difficult time for the publishing industry and for authors in many ways, but this opening, for me, marks a ray of hope.

When a screenwriter writes a screenplay, they are keenly aware of the visual, sonic, and other properties that the medium of film has to offer. Playwrights write for the unique properties of the stage. Songwriters write lyrics for music. But most writers, in my opinion, do not write books. They write texts. They write novels, essays, short stories. Now that the physical book is no longer the most (or only) convenient vehicle for delivering texts, more authors and publishers can begin to take advantage of the book as a medium. In ways, we’ve only scratched the surface. Now that the barricades are opening, educators might also consider broadening the approaches to teaching literacy and the history and craft of writing.

When a screenwriter writes a screenplay, they are keenly aware of the visual, sonic, and other properties that the medium of film has to offer. Playwrights write for the unique properties of the stage. Songwriters write lyrics for music. But most writers, in my opinion, do not write books. They write texts. They write novels, essays, short stories. Now that the physical book is no longer the most (or only) convenient vehicle for delivering texts, more authors and publishers can begin to take advantage of the book as a medium. In ways, we’ve only scratched the surface. Now that the barricades are opening, educators might also consider broadening the approaches to teaching literacy and the history and craft of writing.

A few of the other practitioners of vis lit that I feel a kinship with and admire include: Mark Danielewski, Ruth Laxon, Reif Larsen, Maira Kalman, Graham Rawle, and now J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst. For a more thorough list of books and authors whose visual composition and approach to the book format is integral to the writing, I recommend the annotated list of 22 books that I made for the Designers and Books website.

Much of A Life in Books reflects on the experience of publishing, including blackmailing editors, the printing process, and “the story of the book” itself, its legacy and unpredictable future. What does Bleu’s story say about publishing trends over the past few decades?

Bleu’s history parallels the history of the book, printing, publishing, technological and commercial trends. It all started for him in that junior high school letterpress shop, which even for 1967 was terribly outdated; basically 15th century technology, which meant setting every word of a text by hand, one metal or wood letter at a time. He graduates to the High School of Printing in Manhattan where he learns photomechanical processes, offset printing, and machine binding. As an adult he quickly transitions from being a craftsman writer—a la Ben Franklin and William Blake—to working with small presses, then larger publishing houses, where he is kept at a distance from the mucky business of ink and rollers, and eventually becomes a brand, and if you include his pseudonyms—several brands.

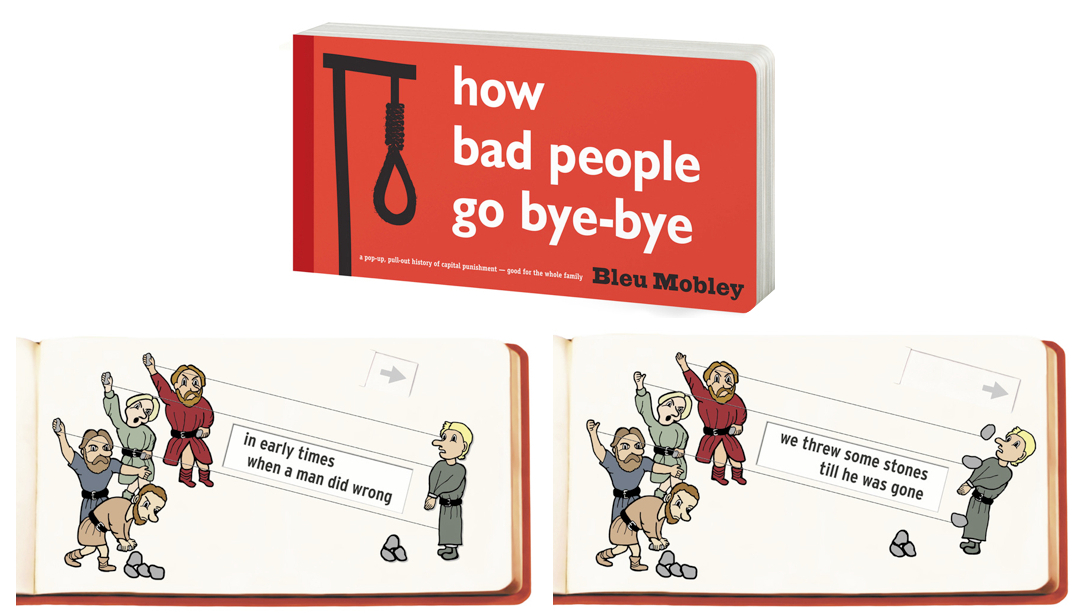

Cover and before and after views of a page from How Bad People Go Bye-Bye, a pull-out, pop up book on the history of capital punishment. Circa 1998.

Bleu despises the very idea of big box bookstores, but as he pursues writing in different genres, he finds himself frequenting these stores, lying down in particular aisles till an idea for a book in that category comes to him. One time, he got an idea for a book in the Children’s section, and when he got up he saw that the Criminology section was right behind him.

He goes on to write other hybrid-genre books like religious porn and culinary murder mysteries.

The Last Bites Trilogy. 1998.

Never one to yearn for new technologies, Bleu is nonetheless quick to adapt, albeit in his own way. In 1998 he published “a spam play” called abyssina estop dystrophy, inspired by those filter-busting, inbox-clogging non-sequitors. The play premiers via an intercontinental performance simulcast live over the web. In time, Bleu becomes addicted to blogging, and becomes a pop-culture TV pundit.

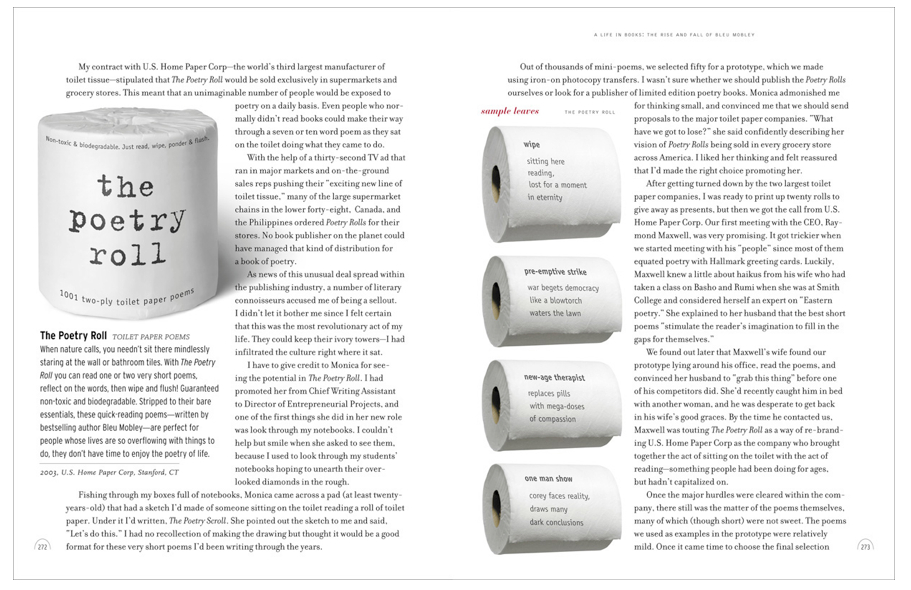

Mindful of ever-shortening attention spans, particularly of younger generations, Bleu migrates from writing 500 page tomes (in which not much of anything happens), to writing episodic book series, flash fiction for young adults, miniature-sized books meant to be sold by the checkout counter, and haiku-length toilet paper poems sold in supermarkets and drug stores (which get pulled from the shelves as soon as complaints start coming in about the contents of the poems).

Page spread from A Life In Books featuring The Poetry Roll. 1001 two-ply toilet paper poems. “Just read, wipe, ponder, and flush.”

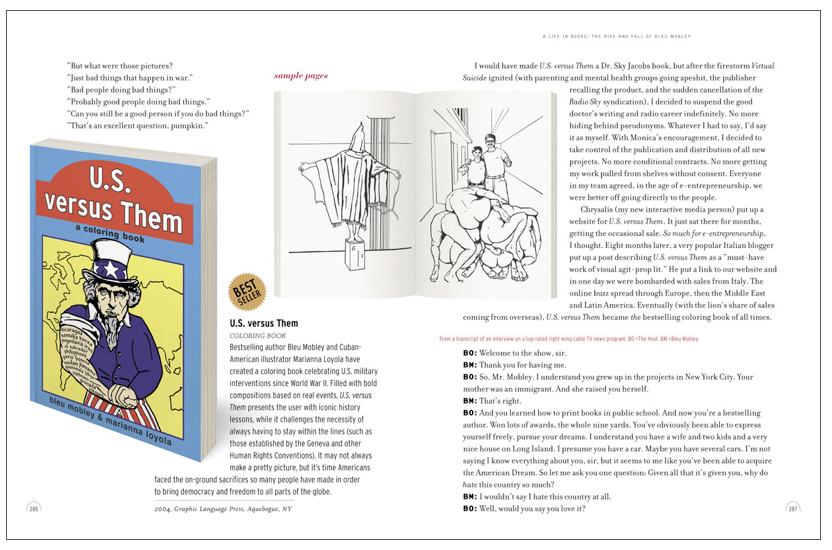

Frustrated by the whims of an increasingly conglomerized publishing industry, and spurred on by his factory of assistants, Bleu joins the “ownership society,” and becomes an entrepreneur, publishing and distributing his own books and book-like products.

Page spread featuring US versus Them: a coloring book, circa 2004.

In 2006, with the addition of engineers and product designers on his team, Bleu develops a prototype for a “multi-sensorial electronic reader” (replete with brain sensors, nose plugs, headphones, and an electronic glove) that allows reader/users to actually smell the smells of a characters in a book, hear their cries and whispers, take hold of what they are holding, and take hold of them, “so nothing at all need be left to the reader’s imagination.”

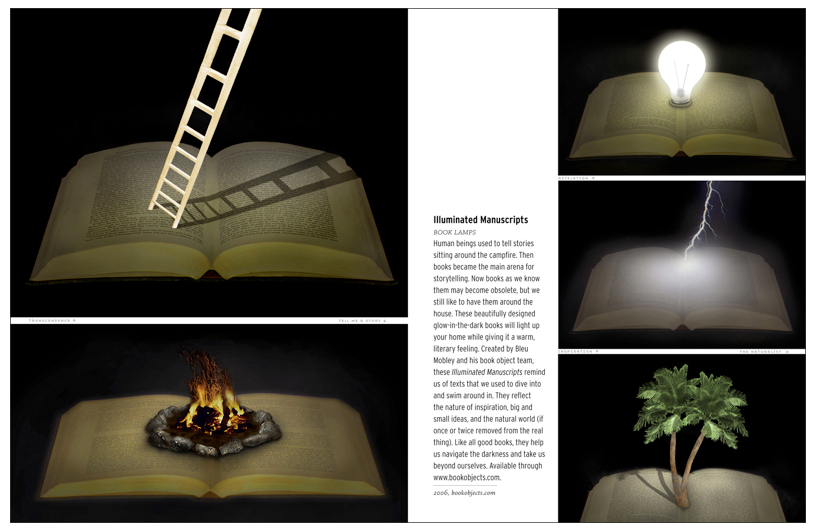

With a growing sense that he’s living in a world where books are not as central to people’s lives as they once were, that reading, deep, contemplative reading is very likely an endangered species, Bleu officially quits writing and turns his writing factory into a laboratory for exploring and entrepreneuring the legacy and future of the book. No more content creation—they zero in on the form and develop a line of book toys for boys, a line of book clothes and accessories, flying books that fly over town and country, and a line of book lamps called Illuminated Manuscripts.

Page spread featuring Illuminated Manuscripts. A line of book lamps that can add a warm, literary feeling to any home. The lamps illuminate the origins of storytelling, the nature of inspiration, and the submersive and transcendent experiences of reading.

Some of these book objects allowed me to play out the flip side of what I was evangelizing before about being at a very exciting moment. I go back and forth between feeling juiced by the possibilities for storytelling these days, and despairing. Even though I’m working with and am fascinated by hybrid platforms that bridge the physical with the digital, I wouldn’t want things to get to the point where every book had to simultaneously be a movie, let alone a video game. I also am nauseated by the notion of the book as an object of nostalgia or deluxe fetish object. That’s not an answer, nor what I’m advocating. We’re in that kind of dual-edged moment. There are more opportunities today for writers and artists and indie presses to publish works that mainstream publishers don’t have the courage to get behind. At the same time, authors are getting screwed by the dematerialized machinery of publishing and other art industries that minimize if not bypass paying “content creators.” It’s fair to say, some of these contradictory concerns manifest themselves in A Life In Books.

Do you have any other upcoming projects?

I’m on sabbatical from my teaching job this coming year, and seem to have a fair amount on my plate connected to A Life In Books. I’m continuing my performance/reading tour which incorporates animations and short films that I’ve been making of Bleu Mobley book excerpts. With the help of a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, I’m developing an enhanced book app edition of A Life In Books, and I’m also working on a traveling exhibition that will present itself as a Bleu Mobley retrospective.

I do have a new book I’m looking forward to starting soon. The surprising thing is—it’s not by me. It’s looking like it’s going to be a Bleu Mobley book. Or maybe several. I had a residency at Rutgers University this past spring, where, among other things, I worked with MFA creative writing students and two undergraduate graphic design classes who collaborated on fleshing out two of Bleu Mobley’s titles based on the excerpts in A Life In Books. It was a thrilling and interesting experience I think for everyone involved. Those two books aren’t finished, but I’m figuring out ways to keep the crowdsourcing of those titles going, along with another one I’ve got posted on www.alifeinbooks.net. Those are collaborative writing experiments, which I will ultimately have to pull together. But the book I’m looking forward to working on most is the one I’ll be writing alone, soon, on behalf of Mr. Mobley.

* * * * * *

Be sure to read Part 1 of IP’s interview with Warren Lehrer. You can purchase A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Indie Bound, or Goff Books.

Lauren White recently graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in History and English. She is serving as assistant editor at Independent Publisher and hopes to continue her career in publishing in New York City. Please email her at larenee [at] umich.edu with any questions and comments.

Lauren White recently graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in History and English. She is serving as assistant editor at Independent Publisher and hopes to continue her career in publishing in New York City. Please email her at larenee [at] umich.edu with any questions and comments.