Book Review : Biography/Journalism

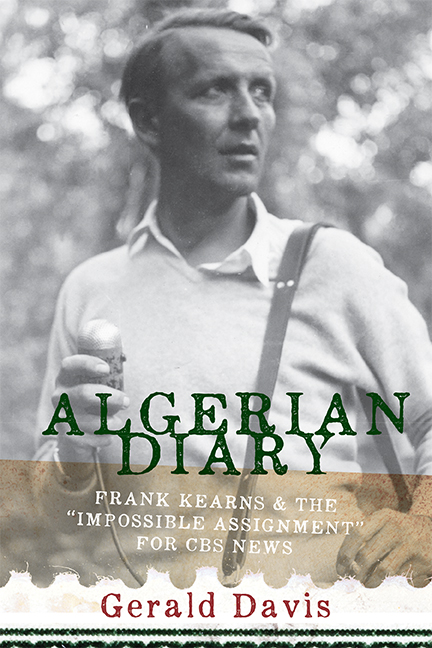

Algerian Diary: Frank Kearns & The "Impossible Assignment" For CBS News

Gerald Davis' book provides a wealth of scattered pieces of the puzzle that made up the 1950’s French-Algerian War (or Non-War), as well as a look at the state of television journalism at that time, before, and beyond.

It highlights the embedded reporter Frank Kearn's diary, (which Davis offers up with immense admiration as a golden cup of journalism), compiled during his challenging first-hand experience living six weeks with the Algerian rebels in the mountains, looking into the eyes of the so called “guerillas” of the Algerian National Liberation Organization as well as the pained souls of the fleeing Arab Immigrants, all in the cause of trying to get “their” side of the story out. (Which may be the reason he lived to tell about it.)

The asides offered up shine a light on the “very different world” of American TV journalism post WWII –accusing it of being overtly used as a powerful arm of propagandist influence for the American government. Davis also presents an impassioned view of the “dumbing-down" of the news in its current evolution.

The oozing glue that holds the book together is a well-meaning tribute by the author to his teacher and mentor journalist Frank Kearns -- the “go to guy” at CBS for dangerous assignments, as well the prized cameraman Yousef (“Joe”) Masraff that accompanied him on the Algerian journey. One thing is for certain, when it comes to journalism the word “luck “ always pops up in the conversation, and it seemed to play a significant role in Kearns' great reporting, as well as the nine lives he possessed (that rolled into 114) in staying alive through it all.

Now to war. There are always two sides. In this one we have the French Government versus the Algerian Nationals. What could be a complicated issue, if you are unfamiliar with the Algerian’s fight for independence from France, Kearns’ reporting boils down to the view the Algerian Nationalists (90% of whom were Arab Muslims) were being treated like second class citizens in their own country. The French Colonial power had swept in more than 100 years earlier and tried to create a mini-France, building up an idyllic land of bucolic rolling farms, creating a European-style world run with French ventures. The rub was that Arab Muslim Nationals were not reaping the benefits equal to that of the Frenchmen. And though they had been saying “enough” and sticking thorns in the side of the French for most of those hundred years, somehow in the early 1950’s they managed to gain enough steam in their resistance to draw some blood from the French government and its' ex-pat settlers. Possibly the card that strengthened the Algerian Nationalists hand was the defeat of the French in Indochina in ’52 and in the Suez region, perpetuating the collapse of the French expansionism in Southeast Asia.

That was the rough and tumble world American foreign correspondent Frank Kearns dropped into, not simply by parachute, but in a slow crawl like an animal through insect-infected mountain scrub in order to report the situation first hand. Kearns found himself sleeping on rocks and on frigid soil, with meager rations and brown drinking water, endlessly ducking air fire from B-26’s, essentially risking life and limb and traveling without a passport or credentials. His diary felt thin -- mainly because his efforts, sometimes nine hours a day -- were plowed into his reporting for CBS. The other prize represented in the book are some of the original sound on film scripts Kearns typed up on oil skin paper while out in the field, showing he had a Director’s command of presenting the stories of the Algerian people’s side of the conflict -- as he saw it – in the most effective packaging to obtain the sympathies of an American audience. How far CBS News strayed from that plan is not presented in the book but would be fascinating to know.

On the French side, Kearns' eyewitness accounts showed the extent of the bloody French “Ratissages”(attacks) conducted against the rebels and the ordinary citizenry, meant to keep them in line -- including burning swaths of their valuable cork tree forests, homes and businesses down to the ground. It all caused a mass exodus of those most vulnerable: widows, children and the frail elderly -- most forced to migrate in rags and barefoot into the hills, or hundreds of miles to neighboring countries such as Tunisia and Morocco.

In contrast, on the Algerian side, Kearns' eyewitness accounts showed the most valuable weapon of the Algerian fighters was belief in their “Just Cause” and the sense of “Unity” they shared with their fellow rebels. In other words, they were fighting with mostly “Heart” and miniscule numbers of weapons confiscated from French soldiers or smuggled in from Egypt. The Algerians had scarce food, scarcer medicine for their wounded, but an unending belief that it was not “if we win the war” but “when we win the war.” And most notably, Kearns expressed in his diary, they had a naïve unending belief that the United States as well as the United Nations would eventually come their aid and free them from the under the thumb of the French. After all, we Americans threw out the British -- and as they saw it we were the keepers and most ardent defenders of the “Beacon of Democracy.”

Davis also presents a condensed version of Kearns' life and his important contributions to CBS News during the developing years -- a time when the networks had bureaus in many foreign cities such as Rome, Paris and Cairo while in a race to report world events with other news outlets such as NBC, and ABC. Kearns bore witness as a reporter on the ground in multiple countries, to the last vestiges of disintegrating control a “handful of Empires” still had over their Colonial outposts. His ballsy frontline reporting continued through the seventies, marking him, according to Dan Rather, during an on-air tribute, “a legend around here.”

In response to the contentious debate over whether Frank Kearns was working as an operative for the CIA while he was reporting for CBS, Davis was cloudy. I found there was not enough evidence presented in the book to make a judgment either way. But, it was a powerful point to be raised and sadly one that haunted Kearns to his death and his surviving family to the present. Whatever the “truth” of the charges, Kearns got the “truth” out on whatever side of a story he was reporting.

Davis’ Algerian Diary is a worthwhile read and presents a plethora of research that helps build a more complete picture of the French-Algerian War and Frank Kearns' vital role in reporting the “Impossible Assignment” for CBS.

* * * * *

Reviewed by Karen Chutsky

Karen Chutsky is the author of The Boy from Tennessee: Young Davy Crockett; editor of Oji: Spy Girls at the Gate; and illustrator of Annabelle's Rescue. Reach her at karenchutsky (at) aol.com

West Virginia University Press

http://wvupressonline.com/node/611

ISBN-978-1-933202-62-4

(March 2016) 208 pgs; $19.99

http://wvupressonline.com/node/611

ISBN-978-1-933202-62-4

(March 2016) 208 pgs; $19.99